Led by Carolina Kuepper-Tetzel (@drckt.bsky.social) and Emily Nordmann (@emilynordmann.bsky.social)

A goal for students in Higher Education is to acquire knowledge and apply it to solve problems, make decisions, and, ultimately, become experts in their area (Persky & Robinson, 2017). A stepping stone to achieve this is to become a successful self-regulated learner which means knowing how to study and manage your time effectively. Unfortunately, when left to their own devices, students will often opt for strategies that feel intuitive and effortless (Bjork, 1994), such as rereading text passages or highlighting text, which may work well in the short term but are, paradoxically, less successful for long-term retention of knowledge (Bjork et al., 2013). Thus, there is a need to support students in adopting more effective study strategies. McDaniel et al. (2020) propose in their Knowledge-Belief-Commitment-Planning (KBCP) framework that before students can commit to or plan the use of study strategies, they need to know about them and believe that they work. Additionally, time management is often a struggle, particularly for new students and is compounded by the greater importance placed on self-directed and independent learning that characterises Higher Education (Wolters & Brady, 2021). To address this, we have integrated these aspects into our curriculum through direct instruction of a) study strategies and b) time management, in addition to planning teaching approaches with effective study strategies in mind.

Direct instruction of study strategies

As a first exposure to study strategies, students should be introduced to the most effective techniques and walked through the benefits of spaced practice, retrieval practice, elaboration, interleaving, concrete examples, and dual coding (Weinstein et al., 2018). As described earlier, students may already have some strategies they use, so the focus will be on explaining how to use the new strategies as part of their own studying routine. In Higher Education, it can be beneficial to highlight the main empirical findings, to discuss why some strategies are better for long-term retention than others, and to provide students with resources for them to explore the strategies on their own (e.g., Effective Study Strategies sway). The book “Ace That Test: A Student’s Guide to Learning Better” by Sumeracki et al. (2023) is on the reading list for all pre-honours students as a study companion.

Direct instruction of time management

Learning how to plan for and prioritise multiple deadlines and competing demands is a key skill that all students must develop. In their review, Wolters and Brady (2021) highlight that time management is associated with reduced procrastination, increased academic performance, and personal well-being, and situate these skills with the framework of self-regulation, encompassing forethought, performance, and post-performance processes. In order to allow students to succeed, it is important to consider where the “hidden curriculum” (Birtill et al., 2024) may need surfacing, for example:

- How many hours a week is considered full-time study?

- How many hours are expected to write an essay

- How long should students spend reading for each lecture?

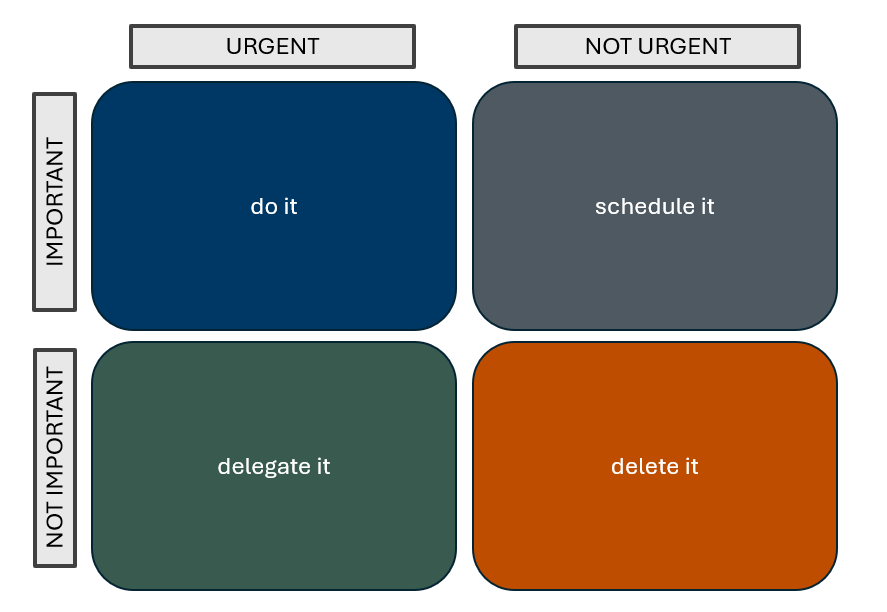

New students (to Higher Education or that level of study) in particular are often uncertain about how long they should spend on each task and this uncertainty can have dire consequence: too little time can lead to under-performance whilst too much may lead to burnout. Time management techniques should also be taught explicitly, for example, the use of to-do lists, backwards planning, and prioritisation techniques such as the Eisenhower Matrix, can help students concretely map out how best to spend their time.

Time management should also be built into assessment guidance. For example, at pre-honours we have introduced flexible submission windows where students are given a week-long window rather than a single deadline for their substantive coursework. Importantly, students are asked to review which day of the window best suits their other commitments and complete an intention to submit form. This form is not mandatory, but it draws on the theory of planned behaviour (Kan & Fabrigar, 2017) to make the planning process concrete and tangible and in doing so helps students understand how to manage multiple deadlines.

Planning teaching with effective study strategies in mind

It is not enough to tell students how to study, they need to experience the strategies themselves to believe that they work. Implementing effective learning strategies in your own teaching is one way to accomplish this. For example, adding short quizzes on previously taught concepts as part of your lecture or providing no-stake quizzes to students to be completed in their own time are ways to integrate spaced retrieval practice in the curriculum which has been shown to increase academic performance (Sotola & Crede, 2021) and decrease overconfidence in students (Kenney & Bailey, 2021).

Changing study habits is difficult and students will revert to less effective and more intuitive shortcuts if they perceive the initiation of a strategy as too challenging (e.g., lack of practice questions) (David et al., 2024). Thus, providing students easy access to practice questions as part of planning teaching can facilitate their own engagement with effective study skills.

References

Birtill, P., Harris, R., & Pownall, M. V. (2023). Unpacking your hidden curriculum: A guide for educators. Quality Assurance Agency. https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/members/unpacking-your-hidden-curriculum-guide-for-educators.pdf?sfvrsn=51d7a581_8

Bjork, R. A. (1994). Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings. In J. Metcalfe & A. P. Shimamura (Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (pp. 185–205). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 417–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823

David, L., Biwer, F., Crutzen, R., & de Bruin, A. (2024). The challenge of change: Understanding the role of habits in university students’ self-regulated learning. Higher Education, 88, 2037–2055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01199-w

Kan, M. P. H., & Fabrigar, L. R. (2017). Theory of planned behavior. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_1191-1

Kenney, K. L., & Bailey, H. (2021). Low-stakes quizzes improve learning and reduce overconfidence in college students. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 21(2). https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v21i2.28650

McDaniel, M. A., & Einstein, G. O. (2020). Training learning strategies to promote self-regulation and transfer: The Knowledge, Belief, Commitment, and Planning Framework. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(6), 1363–1381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620920723

Persky, A. M., & Robinson, J. D. (2017). Moving from novice to expertise and its implications for instruction. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 81(9), Article 6065. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe6065

Sotola, L. K., & Crede, M. (2021). Regarding class quizzes: A meta-analytic synthesis of studies on the relationship between frequent low-stakes testing and class performance. Educational Psychology Review, 33, 407–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09563-9

Sumeracki, M., Nebel, C., Kuepper-Tetzel, C., & Kaminske, A. N. (2023). Ace that test: A student’s guide to learning better. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003327530

Weinstein, Y., Madan, C. R., & Sumeracki, M. A. (2018). Teaching the science of learning. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-017-0087-y

Wolters, C. A., & Brady, A. C. (2021). College students’ time management: A self-regulated learning perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 33, 1319–1351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09519-z

Author biographies

Dr Carolina Kuepper-Tetzel (CPsychol, SFHEA) is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Psychology and Neuroscience at the University of Glasgow, an expert in applying Cognitive Psychology to education, and an enthusiastic science communicator. She leads the TILE Network and is part of the Learning Scientists. She obtained her Ph.D. in Cognitive Psychology from the University of Mannheim, Germany, and pursued postdoc positions at York University in Toronto, Canada, and the Center for Integrative Research in Cognition, Learning, and Education at Washington University in St. Louis, USA. Before joining the University of Glasgow, she was a Lecturer in Psychology at the University of Dundee, UK. She has delivered workshops and talks on research-informed teaching worldwide. Carolina is convinced that psychological research should serve the public and engages in scholarly outreach activities. She is passionate about research-informed teaching and aims to provide her students with the best learning experience possible. She is on the advisory boards for Evidence-Based Education and for a project of the National Institute of Teaching. See her linktree with links to papers, open educational resources, and outreach projects. In her free time, Carolina enjoys books, vinyl records, running, and movies/series.

Dr. Emily Nordmann (PFHEA) is a teaching-focused Senior Lecturer and the Deputy Director Education for the School of Psychology and Neuroscience at the University of Glasgow. Her research predominantly focuses on lecture capture, how it can be used as an effective study tool by students and the impact on students from widening participation backgrounds as well as those with disabilities and neurodivergent conditions. In all her work, she draws on theories of learning from cognitive science and self-regulation, as well as theories of belonging and self-efficacy. Her leadership roles have centred around supporting those on the learning, teaching, and scholarship track acting as centre head for the Pedagogy and Education Research Unit in the School of Psychology and Neuroscience, as well leading the College of MVLS LTS Network. Her teaching is varied although centres on cognitive psychology and beginner data skills in R. She is also Year Lead for our Level 1 undergraduate cohort, an admin role that she has held for the majority of her career and that has informed her research practice greatly. In her free time, Emily enjoys bagging munros, reading, and stand-up comedy.

Pingback: Crynodeb Wythnosol o Adnoddau – 18/3/2025 |

Pingback: Weekly Resource Roundup – 18/3/2025 |