Led by Prof. Sarah Elaine Eaton @saraheaton.bsky.social

In higher education, we find ourselves at a fascinating inflection point. The emergence of powerful artificial intelligence tools has forever changed how we write, research, and create knowledge—forcing us to reconsider long-established notions of academic integrity and plagiarism.

Beyond Traditional Plagiarism

The concept of plagiarism dates back millennia, but its modern understanding solidified after the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, which revolutionized how knowledge was documented and shared. For over 500 years, our conceptualizations of plagiarism have been shaped by technology, with each advancement (e.g., the Internet) introducing new considerations. Before computers, there was no cut-and-paste plagiarism, because cutting-and-pasting did not exist before we used keyboards to copy text from one place to another.

Today, we stand at the threshold of a postplagiarism era—a period where advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence are becoming a normal part of life, including how we teach, learn, and interact on a daily basis.

What is Postplagiarism?

Postplagiarism refers to an era in human society in which historical definitions of plagiarism that focus on cut-and-paste or verbatim copying without attribution are transcended by our relationship with artificial intelligence. In this era, hybrid writing co-created by humans and AI is becoming prevalent, and the lines between human and machine contributions are increasingly blurred.

This does not mean we abandon concerns about academic integrity. Rather, it challenges us to develop more nuanced perspectives that acknowledge how fundamentally our relationship with text, authorship, and knowledge creation has changed.

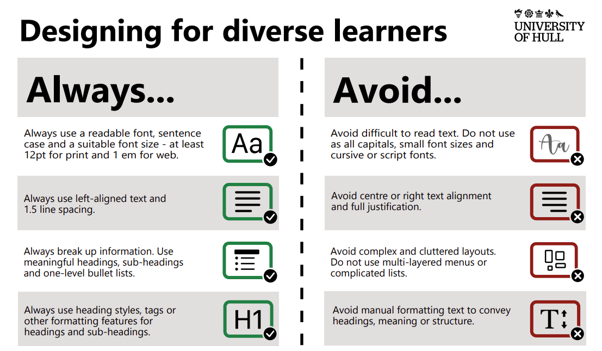

Six Tenets of Postplagiarism

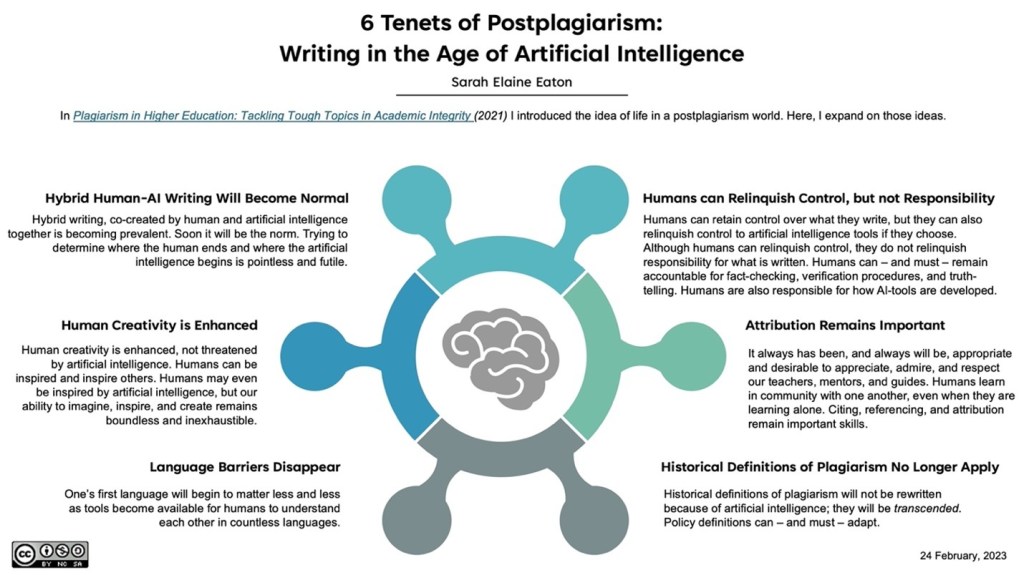

This diagram summarises the 6 tenets of postplagiarism. These are expanded on in the text below.

#1 Hybrid Human-AI Writing Will Become Normal

Hybrid writing, co-created by human and artificial intelligence together is becoming prevalent. Soon it will be the norm. Trying to determine where the human ends and where the artificial intelligence begins is pointless and futile.

#2 Human Creativity is Enhanced

Human creativity is enhanced, not threatened by artificial intelligence. Humans can be inspired and inspire others. Humans may even be inspired by artificial intelligence, but our ability to imagine, inspire, and create remains boundless and inexhaustible.

#3 Language Barriers Disappear

As AI are developed to help us to understand each other in countless languages, then language barriers may be reduced or eliminated.

#4 Humans can Relinquish Control, but not Responsibility

Humans can retain control over what they write, but they can also relinquish control to artificial intelligence tools if they choose. Although humans can relinquish control, they do not relinquish responsibility for what is written. Humans can – and must – remain accountable for fact-checking, verification procedures, and truth-telling. Humans are also responsible for how AI-tools are developed

#5 Attribution Remains Important

It always has been, and always will be, appropriate and desirable to appreciate, admire, and respect our teachers, mentors, and guides. Humans learn in community with one another, even when they are learning alone. Citing, referencing, and attribution remain important skills.

#6 Historical Definitions of Plagiarism No Longer Apply

Historical definitions of plagiarism will not be rewritten because of artificial intelligence; they will be transcended. Policy definitions can – and must – adapt.

Implications for Teaching and Learning

One question we can ask as educators is: how do we respond to this technological revolution? First, we should recognize that the academic integrity ‘arms race’ cannot be won through surveillance and punishment alone. Detection tools for AI-generated content show notable limitations, including false positives that may unfairly penalize students (e.g., Weber-Wulff et al., 2023).

Instead, we might:

- Look for evidence of learning rather than evidence of cheating.

- Design assessments that encourage students to use AI as a supplement to their learning, not a substitute for it.

- Ask students to demonstrate how their work is both better than what AI could have generated alone and better than what they could have produced without AI.

- Create opportunities for students to reflect on their use of AI tools and articulate how these technologies have enhanced their understanding.

Students are not our adversaries in this transition—they are our future. Our goal should be preparing them for a world where AI is ubiquitous, teaching them to use these tools responsibly and ethically.

Moving Forward Together

The postplagiarism era requires us to reconsider fundamental aspects of teaching, learning, and assessment. Rather than fighting a battle against technological change, we have an opportunity to embrace these tools thoughtfully, adapting our pedagogical approaches to prioritize compassion over content, dignity over deadlines, and inclusion as a form of integrity.

By engaging openly with these challenges, we can help our students navigate an educational landscape that increasingly requires them to be not just consumers of information, but collaborative creators of knowledge in partnership with technology.

References

Eaton, S. E. (2023). Postplagiarism: Transdisciplinary ethics and integrity in the age of artificial intelligence and neurotechnology. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 19(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-023-00144-1

Eaton, S. E. (2023, March 4). Artificial intelligence and academic integrity, post-plagiarism. University World News. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20230228133041549

Weber-Wulff, D., Anohina-Naumeca, A., Bjelobaba, S., Foltýnek, T., Guerrero-Dib, J., Popoola, O., Šigut, P., & Waddington, L. (2023). Testing of detection tools for AI-generated text. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 19(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-023-00146-z

Author biography

Sarah Elaine Eaton is a Professor and research chair at the Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary (Canada). She is an award-winning educator, researcher, and leader. She leads transdisciplinary research teams focused on the ethical implications of advanced technology use in educational contexts. Dr. Eaton also holds a concurrent appointment as an Honorary Associate Professor, Deakin University, Australia.