Led by Suzanne Faulkner (SFHEA), teaching fellow in Prosthetics and Orthotics, within the department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, and Dr Kiu Sum, lecturer in Nutrition in the Department of Sport and Health at Southampton Solent University.

The Benefits and Barriers to Playful Learning in Higher Education

Playful learning is an educational approach that integrates elements of play into learning activities, and it is gaining recognition as a powerful pedagogical tool in higher (HE) and further education (FE). It is often defined as an active, engaged, and enjoyable form of learning that encourages curiosity, creativity, and collaboration.

Two sessions led by Suzanne Faulkner: learning about gait through painting feet and analysing footprints, exploring aspects such as step length and walking base width, and Lego Serious Play session with 2nd-year students.

The ‘magic circle’ and play in Higher Education.

The concept of the ‘magic circle’ of playfulness originally introduced by Huizina (1995) and was expanded upon by Salen and Zimmerman (2004), refers to the space where play occurs, explaining how relationships and realities are constructed during play. This occurs through the creation of a specific social situation, where participants cross virtual boundaries and enter another world with accepted and defined rules and codes of practice

Moving from the real world to the ‘magic circle’ involves moving through a liminal space. As learners move through this threshold, they often encounter a transformative process where they evolve from a state of ‘not knowing’ to a state of ‘knowing’, letting go of old ideas to develop and change to embrace and explore new ideas.

One of the key defining features of the magic circle of playfulness is that this is a safe space where mistakes are not only tolerated but encouraged. However, it is important to remember that in the HE/FE context that simply introducing playful activities and games does not create a safe environment, this is developed through developing relationships with their fellow learners over time (Whitton, 2018) to reach a place where individuals feel secure enough to take risks.

Additionally, with a playful mindset, challenges are viewed as opportunities to learn, mistakes are no longer considered as failure, but an opportunity to learn (Guitard et al., 2005). Play facilitates soft fails, fail without consequences. There are not many opportunities for soft fails, or to fail safely in higher education (Forbes, 2021). Doing so helps to build resilience and allows students to take managed risks and develop resilience.

Permission to play

Goffman’s order of interaction discussed in his work “The Presentation of Self in Everyday” (1959), outlines how individuals negotiate their roles and the expectations of others in social interactions. Goffman refers to the “backstage” and “frontstage” dynamics of social life, which ties into permission to play by determining when and how individuals feel free to express themselves or engage in playful behaviour, this is particularly relevant in Higher Education.

Front stage relates to the public persona where people manage their appearance and behaviour to an expected norm, whereas backstage refers to instances where people can be their authentic self.

As such, implementing playful learning in HE and FE settings, both in the UK and globally, presents notable challenges. This blog explores its benefits and barriers.

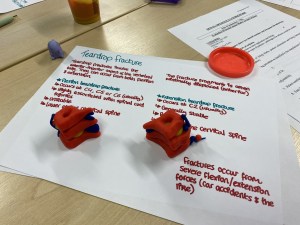

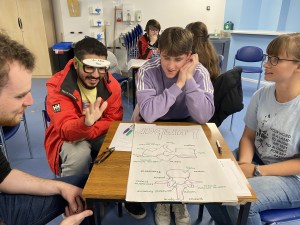

Using the game ‘Who am i?’ with glasses to learn spinal anatomy and playdoh to learn about different types of cervical (neck fractures). Session facilitated by Suzanne Faulkner

Benefits of Playful Learning in Higher Education

- Enhanced Engagement and Motivation

One of the most significant benefits of playful learning is the increased engagement it facilitates. Traditional educational methods can often lead to passive learning, where students are mere recipients of information. Playful learning, on the other hand, encourages active participation, making learning more enjoyable and stimulating. Pivec (2007) highlights that when students engage in playful activities, such as role-playing, gamification, or problem-solving challenges, they are more likely to remain motivated and enthusiastic about their studies. - Development of Critical Thinking and Creativity

Playful learning encourages students to ‘think outside the box’ and explore new ways of solving problems. Activities such as games, simulations, or interactive workshops – particularly when real-world problems are posed – require students to apply critical thinking, adapt to new information, and work collaboratively. This process helps to foster creativity, as students are encouraged to experiment with ideas and approaches in a low-stakes environment. In HE/FE, where innovation and original thinking are highly valued, these skills are essential for academic and professional success. - Fostering Collaborative Learning

Playful learning often involves group activities, which can enhance collaborative work. In HE and FE settings, group projects and peer-to-peer learning are integral parts of the academic experience. Playful learning settings, such as team-based games or interactive exercises, encourage communication, teamwork, and the sharing of ideas. These social learning environments can help students build relationships, strengthen networks, and develop interpersonal skills that are valuable in both academic and professional contexts. - Stress Reduction and Well-Being

The pressure of university life can be overwhelming, and students may experience stress, anxiety, or burnout. Playful learning offers a means to mitigate these challenges by creating a more relaxed and enjoyable atmosphere for learning. Importantly, students who engage in play are more likely to overcome challenges and think of new, innovative solutions (Walsh, 2015). Engaging in play-related activities can trigger the release of dopamine, associated with feelings of pleasure and reward. This can lead to improved mental well-being and a greater sense of fulfilment in academic pursuits.

Barriers to Playful Learning in Higher Education

- Perceived Lack of Academic Rigour

One of the most significant barriers to adopting playful learning in HE is the perception that it lacks academic rigour. Many HE institutions prioritise formal assessments, research output, and traditional teaching methods. As a result, there is a reluctance to embrace playful learning, which is sometimes viewed as trivial or not serious enough for academic environments. Some educators and students may also feel that playful learning is incompatible with the expectations of higher education, which often emphasise critical thinking, discipline-specific knowledge, and assessment-driven learning. - Resource Constraints

Implementing playful learning in HE settings can be resource-intensive and expensive. Games, simulations, and other playful activities require time, effort, and financial investment to design and execute effectively – not forgetting space to store the resources and manage them. Universities may face budget constraints that limit their ability to integrate these methods into the curriculum, which often means proponents of play end up funding resources from their own pockets. Additionally, academic staff may require training in how to facilitate playful learning experiences, which can further strain institutional resources (Lester & Russell, 2010). This is particularly challenging for institutions with limited resources or those focused on large-scale lectures rather than interactive or experiential learning. - Cultural and Institutional Resistance

Despite the evidenced benefits of play in HE, resistance to play in HE persists (James, 2022), with transmissive learning often the unquestioned norm in academia (Koeners & Francis, 2020). There may also be cultural resistance to playful learning in HE/FE In many academic environments, especially in more traditional or conservative settings, there is an entrenched belief in the value of formal instruction and the separation between work and play. A significant problem identified is misunderstanding the role of play in HE. The continuing stigma of play, thought of as frivolous, lacking rigour and a loss of credibility continues to be barriers faced by the proponents of play (Koeners & Francis, 2020). The shift towards a more playful and interactive approach may be met with scepticism or resistance from both faculty and students who are accustomed to conventional teaching methods. This can create barriers to the widespread adoption of playful learning practices, as some educational stakeholders may fear that such approaches could undermine the perceived value of the academic experience. - Assessment Challenges

Playful learning can pose challenges when it comes to assessment. Traditional forms of assessment, such as exams and essays, do not always align with the experiential and dynamic nature of playful learning activities. This mismatch between learning and assessment methods can make it difficult to measure the outcomes of playful learning accurately. Additionally, is appears, there is a lack of established frameworks for evaluating the effectiveness of playful learning, which may deter educators from adopting it in their teaching practices.

Conclusion

Playful learning offers numerous benefits in HE and FE settings, including increased engagement, the development of critical thinking and creativity, enhanced collaboration, and improved well-being. However, its implementation faces significant barriers, such as the perception of a lack of academic rigour, resource constraints, cultural resistance, and challenges related to assessment. To overcome these barriers, institutions must create supportive environments that value innovative pedagogies (and the academics/teaching staff that spearhead these), provide adequate resources for playful learning initiatives, and develop new assessment frameworks that align with these approaches. With the right support, playful learning has the potential to significantly enrich the HE/FE experiences and prepare students for the dynamic and evolving demands of the future.

References:

Forbes, L. (2021). The Process of Playful Learning in Higher Education: A Phenomenological Study. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 15, pp. 57–73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v15i1.6515

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday.

Huizinga, J. (1955). Homo ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Boston, MA: The Beacon Press.

Guitard, P., Ferland, F., & Dutil, É. (2005). Toward a Better Understanding of Playfulness in Adults. OTJR: Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 25(1), pp. 9–22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/153944920502500103

James, A. (2022). The Use and Value of Play in HE: A Study. Independent scholarship supported by The Imagination Lab Foundation. Available at: https://engagingimagination.com

Koeners, M. P. & Francis, J. (2020). The physiology of play: Potential relevance for higher education. International Journal of Play, 9(1), pp. 143–159. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2020.1720128

Salen, K. & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of play: Game design fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Walsh, A. (2015). Playful Information Literacy: Play and Information Literacy in Higher Education. Nordic Journal of Information Literacy in Higher Education, 7(1), pp. 80–94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15845/noril.v7i1.223

Whitton, N. J. (2018). Playful Learning: Tools, Techniques, and Tactics. Research in Learning Technology, 26, pp. 1–12. ISSN: 2156-7069. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v26.2035

Author Biographies

Suzanne Faulkner (SFHEA) is a teaching fellow in Prosthetics and Orthotics, within the department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, she is also a facilitator trained in the LEGO® Serious Play® (LSP) methodology. Suzanne is passionate about enhancing the student experience by focusing on improving student engagement, utilising social media in learning and teaching and incorporating playful learning. She has been nominated and shortlisted for several teaching excellence awards and is currently undertaking an EdD, evaluating the use of LSP to enhance participation of students who have English as an additional language in group work activities.

X: @SFaulknerPandO

Bluesky: @sfaulknerpando.bsky.social

Dr Kiu Sum is a Lecturer in Nutrition in the Department of Sport and Health at Southampton Solent University. With a BSc(Hons) and MRes in Human Nutrition, Kiu’s mixed-methods research includes workplace nutrition, public health nutrition, and nutritional behaviour. Kiu’s PhD explored doctors’ and nurses’ nutrition during shift work. Aside from nutrition, she is a pedagogy researcher focusing on student engagement and partnerships, assessments and feedback.

Kiu is a Registered Nutritionist (Nutritional Science) with the Association for Nutrition (AfN) and a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. Kiu is a member of The Nutrition Society, Chair of the Institute of Food Science and Technology’s South East Branch Committee, the Communications Officer of the UK Society for Behavioural Medicine’s Early Career Network. She serves as Secretary at the RAISE Network, where she also convenes the Engaging Assessment and the Early Career Researchers Special Interest Groups. With an interest in Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI), Kiu serves on ALDinHE’s Steering Group and leads the EDI Working Group.

X: @ KiuSum

BlueSky: @kiusum.bsky.social

Looking forward to joining in! 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: #BecomingEduccational #Shoutout for Playful Learning | Becoming An Educationalist

Pingback: #LTHEchat 319: Winning the Learning Game with Game-based Learning | #LTHEchat